Second-hand books marked up

Thoughts on storytelling, literature, histories, creativity and the authentic self.

Creating a logo for my podcast page.

George Eliot states in her opening line to Silas Marner, the Weaver of Raveloe. (1861): ‘In the days when the spinning wheels hummed busily in the farmhouses…’ creating an interior scene of pastoral efficiency.

Silas Marner (the main character) is introduced to the reader. ‘In the early days of this century, such a linen-weaver … worked at his vocation in a stone cottage that stood among the nutty hedgerows and the neighbourhood of Lantern’s Yard. This is described as ‘nestled in a snug well-wooded hollow,’ with a church nearby. Setting the scene of an industrious pastoral landscape, somewhere nearer the 1810s, which is fifty years prior to the story’s publication.

To show how quickly the industrial revolution cascaded over those living through this era, there is a scene where Eliot depicts Silas’s return to his old neighbourhood at Lantern Yard after fifteen a year absence. There, he finds that old houses have been ‘swept away’ and in their place is a large factory. Silas states that the place has become ‘a great manufacturing town.’

His shock at the new factory emphasises the dehumanisation effect factories had on the workforce cannot be understated. A place where men and women were ‘streaming for their mid-day mean.’ Silas’s daughter, Eppie, describes the place as a ‘dark, ugly place,’ and it ‘hides the sky from view.’ The change that has occurred in Lantern’s Yard exemplifies the dread with which the industrialisation process was witnessed and depicted in realist fiction.

As with other fiction writers at this time, Eliot focuses on the ‘crowding’ of women and men at the factory gates, and when Silas returns that evening to his cottage in the Midlands, he tells how ‘The old place is all swep’ away.’

What’s interesting in this section of the novel is Eliot’s depiction of the new ways of factory working. Most notably she could have been influenced by the many spinning and cotton mills springing up over the countryside at that time. Another facet of this is the abject horror as to what was happening with regard the location of work and the changing landscape.

The way in which traditional craft and skilled work in the home was replaced with large factories as places of work and the pace at which this change happened could perhaps be synonymous with the scale of change we see again today. As we move from the heavily industrialised reliance on factory work and the way in which large factories paved the way for even bigger offices traditionally used in much the same way as factories. A move which now capitalises on new technologies and more remote ways of working. Could it be that the way in which businesses operate are turning a corner once again. It’s too early to tell how working lives will be shaped in the near future, but of interest may be remote robotics and virtual reality.

Current ideas surrounding WFH virtual reality teams: https://www.zmescience.com/research/technology/vr-companies-create-interactive-virtual-offices-and-event-solutions-for-a-new-era-of-remote-work/

UK-based start-up Extend Robotics VR controlled robotic arm: https://www.theengineer.co.uk/extend-robotics-unveils-new-vr-controlled-robotic-arm/

And because we need a work/ life balance. https://mercecardus.com/how-virtual-reality-will-supplant-the-film-going-experience/?utm_source=ReviveOldPost&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=ReviveOldPost

I’m currently reading Thomas Hardy’s Far From the Madding Crowd. One thing that strikes me is his poetic language, the rich imagery which is rooted in the landscape of agrarian life.

This is in sharp contrast to the Dickens’ novels which I’m more familiar with. Dickens considers the life of progress, the industrious Victorians and the landscape is very much more concrete and urban.

What’s perhaps more interesting is that both authors were writing in a similar time period: Charles Dickens b.1812 – d.1870; and Thomas Hardy b.1840 – d.1928

Charles Dickens, it could be said, belonged to a time when progress was new and exciting. His upbringing in the city was besieged with poverty. George III was on the throne when he was born, and Queen Victoria when he died. He was more enthused by progress and excited by industriousness. This passion and cynicism is evident in his writing. He talks about the destruction of Staggs’ Garden through the passing comments of local residents who watched the building of the railway through the countryside. While his characters may have lamented the loss of such a beautiful piece of land, nothing, it seems, stands in the way of progress.

For Hardy, on the other hand, while born after Dickens, the sweeping progress had mostly passed him by. The main railways had already been built, the modern urban city was already industrious. He didn’t talk about station time, but we saw Farmer Oak struggle with a pocket watch, always slow, fast or lagging in some way. We see him checking the position of the stars, and thus he knows the when the lambing season begins, he can tell the time through the night sky. Hardy is showing us the connection to the universal world; he’s saying, ‘But look what we’re leaving behind.’

Both writers in their own way, Dickens with his exaggerated pathos of the situation of progress and Hardy with his lyrical prose are giving us a glimpse into the landscape of their time in different ways. Reading these writers from a business perspective highlights the way in which the authors have captured the idea of progress in what we often refer to as the first age of contemporary globalisation.

There is another author from this time who also deserves a business perspective on her writing, Elizabeth Gaskell, 1810-1865. This will be the subject of another blog post.

In 1485, Richard III, the last of the Plantagenet kings died in the Battle of Bosworth Field. The battle began early morning on 22nd August and was over by noon. His defeat marked the end of the Wars of the Roses and of the Middle Ages.

You can be sure they wouldn’t be setting their watches to a precise time for battle to commence. Rather, at first light, they would gather and attack when they felt there was enough light.

Smaller Timepieces

Just as the new dawn of the Tudor age began in Britain, across the channel in Nuremberg, Germany, Helen Henlein gave birth to her second son, Peter. He would become one of a group of innovators and inventors of this time. At the turn of the 16th century, portable watches were coming into being. Innovators were creating ever smaller mechanisms. Although Henlein wasn’t the first to create a portable watch, he is (erroneously) credited with adding a main component; the mainspring.

Although a mobile watch was light enough to be carried around, it wasn’t very accurate; they could lose hours of time sometimes within one day. Subsequent improvements by peers allowed the device to keep better time.

Peter Henlein died in 1547 — the same year of the death of` another British monarch, Henry VIII. He left a legacy upon which timepieces could be built. By the time of his death, he was a well-renowned watchmaker. He’d supplied aristocrats far and wide in the design and building of smaller clocks.

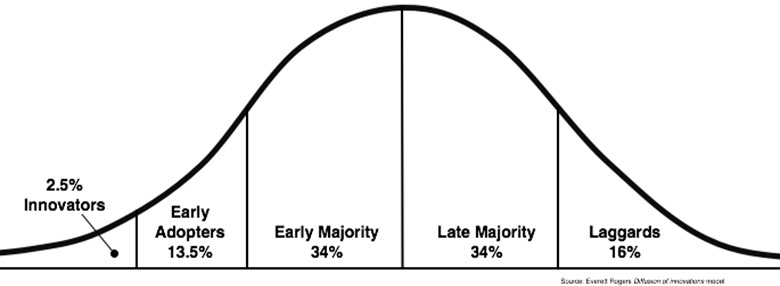

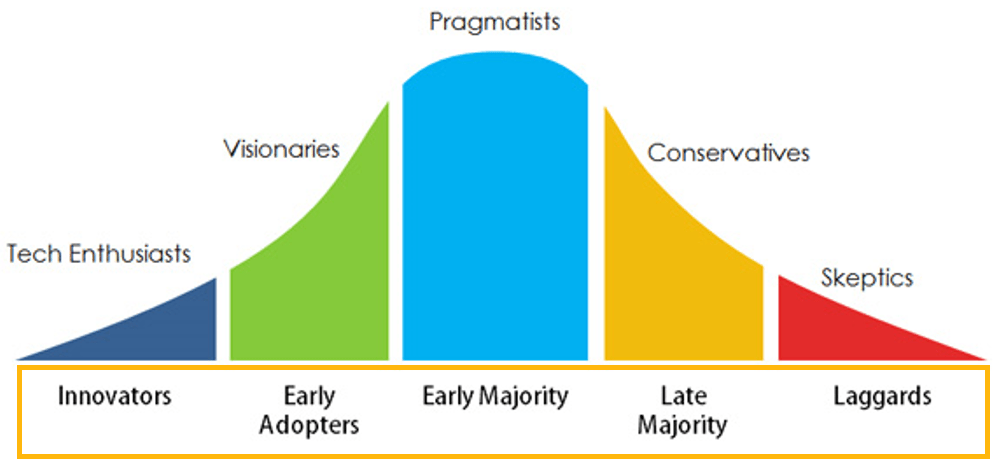

The area of diffusion is geographically and socially bound. Larger, mass market population are left out, not only by distance, but also by resources, such as money to purchase high quality and expensive products. The market qualifiers for these pieces at this time would be the aristocratic and wealthy, who would have travelled around Europe freely, frequenting European courts. The diffusion process would have been carried through word of mouth in the highest echelons of societal grandiose.

Note to the diffusion model: in the case above, the 2.5% of innovators would consist of the aristocracy, perhaps also some minor aristocrats and wealthy individuals.

The Accuracy of the timepiece

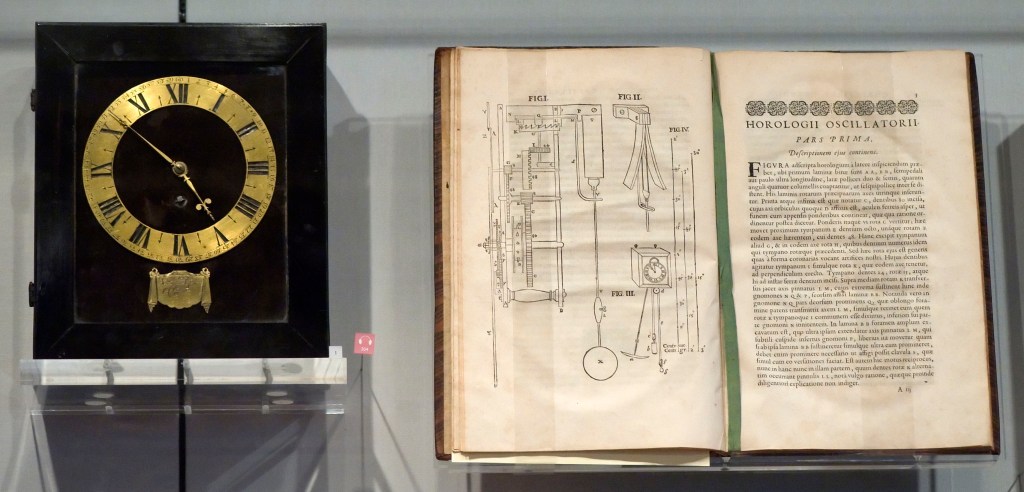

Building on the ideas of Galileo, the Dutch scientist, Christiaan Huygens invented the most accurate clock to date in 1656. He utilised the regular oscillations of a weighted pendulum, regulated by a mechanical device. he was an all round inventor, and author of Horologium Oscillatorium: Sive de Motu Pendulorum ad Horologia Aptato Demonstrationes Geometricae (Latin for “The Pendulum Clock”): or geometrical demonstrations concerning the motion of pendula as applied to clocks”) published in 1673, shows the depth of knowledge it takes for an inventor to be invested in their new ways of doing things, or inventing, creating the process involved is intensive, at least in the beginning would seem to be. This is where we find the idea generation, the creativity process is an integral part of innovation academia.

What is int”eresting about Christiaan, is that he was the inventor of the process. He didn’t build the mechanism. He gave the design to a clock maker who made a clock to his specifications. In this status on, you would wonder who is the innovator, the creator of the design or the maker of the design? But still, this wasn’t a particular breakthrough in anything that would have market value, customer appeal or would take the timepiece any further through the diffusion process.

Source of information for Christiaan Huygen’s book. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horologium_Oscillatorium

The Balance Spring

Balance spring watches (1660) were a vast improvement on the accuracy of earlier timepieces, a balance spring mechanism controlled the speed of the separate pieces of a watch with the help fo a regulator, which ensured the mechanism remained as consistent as possible. Robert Hooke and Christian Huygens are both credited with this invention.

Thomas Tompion engineered the most effective regulator of time around 1680. In partnership with the scientist, Robert Hooke, they created an early type of spring with double balances geared together in order to eliminate errors of motion. However, this incremental type of innovation hasn’t (yet) translated to mass movement for people to need watches, particularly as one goes further down the class movements, people don’t make arrangements to meet for tea or sandwiches, they work when it gets light, probably in agriculture and they go about their daily business, ticking off a to-do list, rather than a time-related schedule. Then, they finish work when it gets dark. If they need to know the time, there are clock towers in nearby villages and towns. When did our obsession with needing to know what the time is actually take off in earnest — when did the diffusion process amplify?

Railway Time

Until the latter part of the 18th century, each town had its time measured by a local sundial, and as a result, local times would differ by several minutes. It was difficult for the ever-increasing rail industry to organise efficiently. Although, it’s now termed ‘Railway Time’. The first recorded occasion was when different local mean times were synchronised for a standard time across the country. The key goals behind introducing railway time were to overcome the confusion caused by have local times throughout the country, in each station stops across the expanding railway network. This would also work to reduce incidences of accidents which were becoming more frequent as the number of trains and journeys were using the lines.

As more people relied on train journeys either for travelling to work or for using them to take holidays in the country, as the newly found leisure time the Victorians had was increasing, so it became necessary to set your timepiece to the new standard time. Cue the realisation for the need of watches. However, as with most new technologies, it’s the advent of war that realises the process of diffusion. In 1916, it was imperative to coordinate efforts in campaigns and thus the wristwatch became an item that was invaluable in this sense, although wristwatches had been around, particularly in European markets since the 1850s, this was when the wristwatch found its way into the American market.

Let’s look at the area of diffusion process again.

The early adopters, on the other hand are those who look to the innovators, and people who can use word of mouth to illustrate the innovation. These could also include means of distribution and once the product can be seen, it can be purchased by those early adopters. Therefore, key to the early marketing strategy is that of distribution or visibility.

The early majority are keen to purchase products as they have been used, as in tried and tested and been around for a bit. At this point, the diffusion process is almost complete. It’s worth mentioning that a product can spend a good part of its lifespan here. For example, with wristwatches, let’s take the year of 1880 as a typical year when early adopters were using the technology, the years between 1880 and 1900 when the early majority were using watches. From 1900 to 1940, the late majority were purchasing wristwatches, and when your watch broke, you had it repaired or bought a new one. Everyone has a wristwatch and the object has become part of every day life.

From the UK perspective, in the 1850s, local time was being replaced with standard time, and this became law in 1880 by Royal Assent. We’ve considered the ‘innovators’, those who kept clocks, portable clocks, watches in order to tell the time, rather than having to rely on the more traditional sundial. These are the people who like ‘novel’, they purchase new technologies and will pay premium for the product. They are also the influencers of opinion. As we’ve seen, in the past, it has been royal houses and houses of wealth who can afford such luxuries. In contemporary society we have ‘influencers’ and ‘celebrities’.

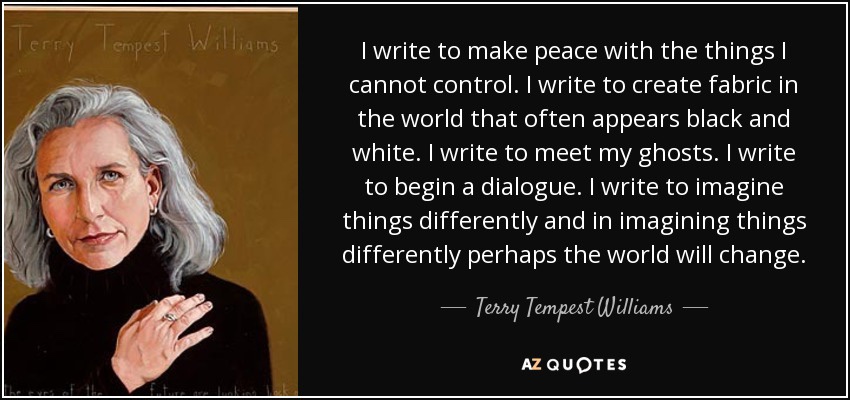

Terry Tempest Williams wrote about “Why I Write” whereupon she lists many reasons:

Writing helps us to make sense of the world, to uncover things that are unknown. It can lead to a story of discovery, to create words in a void and to begin the conversation.

She asks: Why do you write?

It is just after 5am. I was dreaming about the old house by the sea, Nikita was there, and we had an Alsatian dog, Bernie, who we were taking for a walk. I put on my gloves, warming my hands and we made our way to the food shack; a small hut at the end of the walk along the beach, serving hot food. Their homemade lentil soup is the best. Comfort served with no bells or whistles in a polystyrene cup.

The snowfall began just as I had started reciting why I write, snowflakes on our coats, on our eyelashes and in Bernie’s mouth as he licked the wide open space; he loves running along the beach, into the water, fetching his ball, collecting sticks.

I write to free the words, the images in my mind to create meaning in the world. What is your reality? Is it the same as hers? What about his? I write to try to make sense of what motivates the murderer, the narcissist; to give a name to nameless people, a voice to the voiceless, to understand why they wait in the shadows for us to join them. I write as a way of travelling to the past, remaking the present and entering the future. What would it be like if? What would have happened in the past if? What if everything we know about our past is built on the graves of those who were slain for knowing the truth? And wonder who has tampered with our reality, a questioner, a non-believer, homeless, wandering in the dark.

I hunch my shoulders and put my head down as the wind whips the snow and it falls ever harder. Nikita’s rosy cheeks are sometimes my only joy in this world and her eyes sparkle with the bright light she was born with. I write because this is the world I want to see.

I write because there are more answers and more questions than will ever be uttered. I write out of ignorance of what some of those answers are. I write because a blank page will haunt me and that in the dying days, I will say, I wish I’d left fewer blank pages in the world. I write in the morning in dreams, I write in the evening sipping hot chocolate. I write knowing there is failure in every word. I write with the optimism of one who doesn’t know when to stop.

And breathe.

Why do you write?

What are you writing during lockdown? If you’re like me, not very much at all. There has been much upheaval in terms of making lifestyle changes. The work I had was cancelled. With the closure of local parks and the gym being closed, finding motivation to do very much was difficult.

I took a couple of months off from writing, house renovations and plans were pushed back. Instead I concentrated on being creative. I got out my sewing machine, made some clothes, cut out sewing patterns for my next projects and learned to knit. Then I made myself a to-do list, and slowly but surely, I’m working my way through it. And I added many new books to my TBR pile, both fiction and non-fiction.

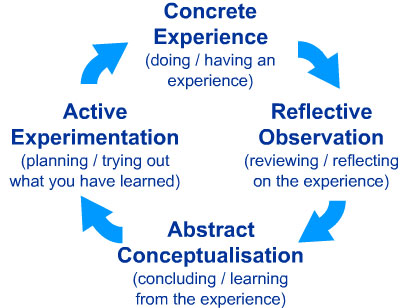

Reflecting on learning is an ongoing process. The EBI project already requires some amount of reflection and some thought on where those reflections will enable me to take the project forward some more. Therefore, it’s important to understand the specifics of reflection in the workplace.

Kolb’s is the most commonly used model to analyse the process of reflective thinking. From our own concrete experiences, we take time to review the processes — some of this will happen naturally, but that kind of reflection tends to be lost in the annals of ‘stuff that didn’t quite go right, must try again.’ The deliberate reflection gives you the opportunity to draw some conclusions along the lines of a different path, and then the active phase of the cycle, where you can try out something different. This is weak in the area of including others in your reflections. Other people do affect how you carry out work / social tasks and shouldn’t be neglected from reflective activities.

Pedlar’s process is a little more experiential-based and can be applied simply — possibly simpler than Kolb’s, which goes a long way to describing the process, but which is vague in the actions that are taken by the process.

Pedlar’s process shows a beginning and an end to the process, which is far more satisfying to those who like to know how and where the process can lead. It asks about a specific action and thoughts that happened at the time and for you to spot any recurring behaviours from yourself. The reflective process goes something along the lines of:

There is a clear line of linkages between the experience and the action that will be taken. This is a process that I will do in certain stages on the EBI. The first of which will be fully explored after meetings with the stakeholders.

In addition to this, Marshall did some work on arcs of attention. The inner arc reflects reflects our patterns of behaviours, thoughts and language we use; our conceptualisation of reality — our assumptions and how we respond to others. The outer arcs of attention refer to the context of attentions and our construction of reality, making sense of and responding to changing situations.

Reflection. I have been on my MBA journey for two years. Some highlights include:

This forms part of my reflective practice for 1.2 of my MBA journey.

This blog should have been started two years ago when I began my MBA journey. But I didn’t have the time, didn’t have the inclination, and was still busy wrapped up in my old life. And that seems a strange thing to think about because in just over two years, the focus of my attention has shifted dramatically.

Then. Before. I was caught up in life’s roiling ups and downs, oftentimes not my own. I was the main carer for my mother. My daughter needed a taxi (me) and attention.

Now. I read articles and business papers. I focus on the ideas, the concepts. I think about work, my colleagues and life is meaningful in a different way.

Then. I read supermarket two for one offers. Thrillers. Science Fiction. Fabulous page-turners.

Now. I listen to audiobooks such as Love in the Time of Cholera and have several hefty tomes on organisational management, many themes on chaos and ideas about consciousness.

Then. I didn’t have a focus for my blogs. I started them, I stopped them. I demolished them. Started another. And left them to wither somewhere in the bits and megabits landfill.

Now…. I make no promises to myself. Let’s see where this new journey takes me.

Of course, it was Aristotle who coined the phrase but Mary Poppins made it popular.