In 1485, Richard III, the last of the Plantagenet kings died in the Battle of Bosworth Field. The battle began early morning on 22nd August and was over by noon. His defeat marked the end of the Wars of the Roses and of the Middle Ages.

You can be sure they wouldn’t be setting their watches to a precise time for battle to commence. Rather, at first light, they would gather and attack when they felt there was enough light.

Smaller Timepieces

Just as the new dawn of the Tudor age began in Britain, across the channel in Nuremberg, Germany, Helen Henlein gave birth to her second son, Peter. He would become one of a group of innovators and inventors of this time. At the turn of the 16th century, portable watches were coming into being. Innovators were creating ever smaller mechanisms. Although Henlein wasn’t the first to create a portable watch, he is (erroneously) credited with adding a main component; the mainspring.

Although a mobile watch was light enough to be carried around, it wasn’t very accurate; they could lose hours of time sometimes within one day. Subsequent improvements by peers allowed the device to keep better time.

Peter Henlein died in 1547 — the same year of the death of` another British monarch, Henry VIII. He left a legacy upon which timepieces could be built. By the time of his death, he was a well-renowned watchmaker. He’d supplied aristocrats far and wide in the design and building of smaller clocks.

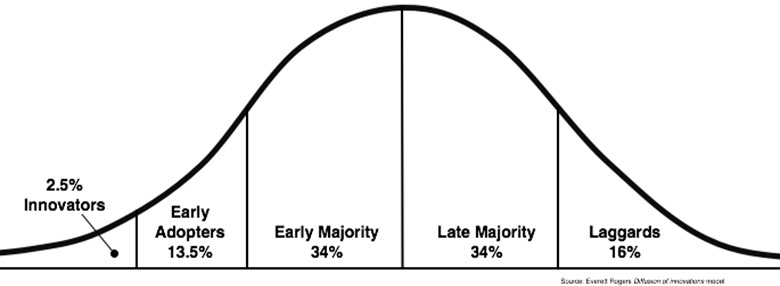

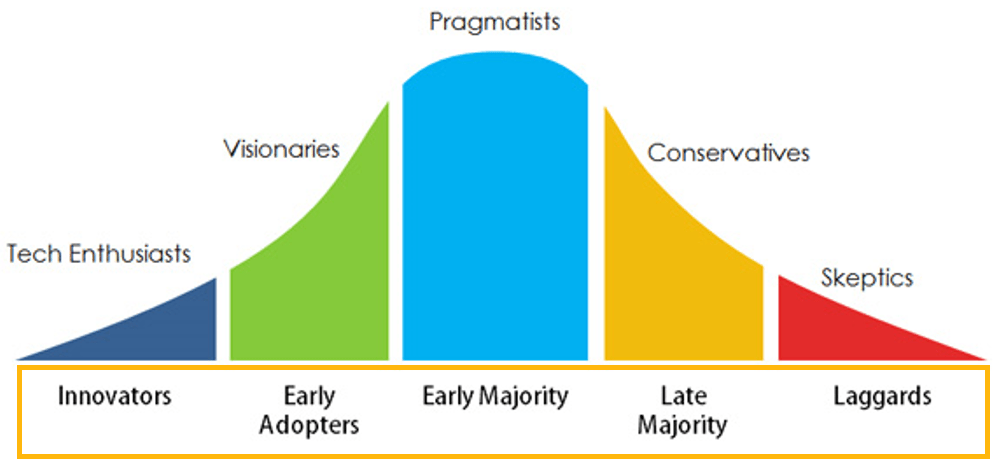

The area of diffusion is geographically and socially bound. Larger, mass market population are left out, not only by distance, but also by resources, such as money to purchase high quality and expensive products. The market qualifiers for these pieces at this time would be the aristocratic and wealthy, who would have travelled around Europe freely, frequenting European courts. The diffusion process would have been carried through word of mouth in the highest echelons of societal grandiose.

Note to the diffusion model: in the case above, the 2.5% of innovators would consist of the aristocracy, perhaps also some minor aristocrats and wealthy individuals.

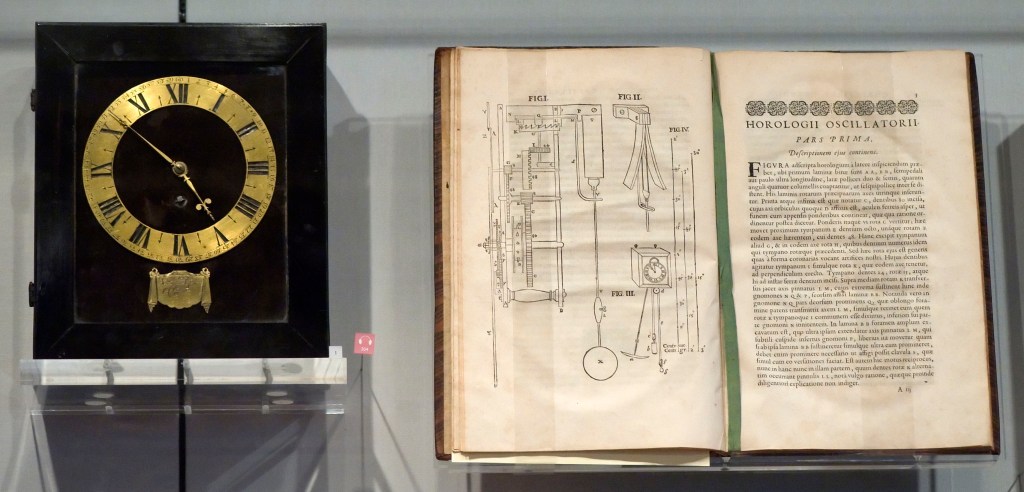

The Accuracy of the timepiece

Building on the ideas of Galileo, the Dutch scientist, Christiaan Huygens invented the most accurate clock to date in 1656. He utilised the regular oscillations of a weighted pendulum, regulated by a mechanical device. he was an all round inventor, and author of Horologium Oscillatorium: Sive de Motu Pendulorum ad Horologia Aptato Demonstrationes Geometricae (Latin for “The Pendulum Clock”): or geometrical demonstrations concerning the motion of pendula as applied to clocks”) published in 1673, shows the depth of knowledge it takes for an inventor to be invested in their new ways of doing things, or inventing, creating the process involved is intensive, at least in the beginning would seem to be. This is where we find the idea generation, the creativity process is an integral part of innovation academia.

What is int”eresting about Christiaan, is that he was the inventor of the process. He didn’t build the mechanism. He gave the design to a clock maker who made a clock to his specifications. In this status on, you would wonder who is the innovator, the creator of the design or the maker of the design? But still, this wasn’t a particular breakthrough in anything that would have market value, customer appeal or would take the timepiece any further through the diffusion process.

Source of information for Christiaan Huygen’s book. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horologium_Oscillatorium

The Balance Spring

Balance spring watches (1660) were a vast improvement on the accuracy of earlier timepieces, a balance spring mechanism controlled the speed of the separate pieces of a watch with the help fo a regulator, which ensured the mechanism remained as consistent as possible. Robert Hooke and Christian Huygens are both credited with this invention.

Thomas Tompion engineered the most effective regulator of time around 1680. In partnership with the scientist, Robert Hooke, they created an early type of spring with double balances geared together in order to eliminate errors of motion. However, this incremental type of innovation hasn’t (yet) translated to mass movement for people to need watches, particularly as one goes further down the class movements, people don’t make arrangements to meet for tea or sandwiches, they work when it gets light, probably in agriculture and they go about their daily business, ticking off a to-do list, rather than a time-related schedule. Then, they finish work when it gets dark. If they need to know the time, there are clock towers in nearby villages and towns. When did our obsession with needing to know what the time is actually take off in earnest — when did the diffusion process amplify?

Railway Time

Until the latter part of the 18th century, each town had its time measured by a local sundial, and as a result, local times would differ by several minutes. It was difficult for the ever-increasing rail industry to organise efficiently. Although, it’s now termed ‘Railway Time’. The first recorded occasion was when different local mean times were synchronised for a standard time across the country. The key goals behind introducing railway time were to overcome the confusion caused by have local times throughout the country, in each station stops across the expanding railway network. This would also work to reduce incidences of accidents which were becoming more frequent as the number of trains and journeys were using the lines.

As more people relied on train journeys either for travelling to work or for using them to take holidays in the country, as the newly found leisure time the Victorians had was increasing, so it became necessary to set your timepiece to the new standard time. Cue the realisation for the need of watches. However, as with most new technologies, it’s the advent of war that realises the process of diffusion. In 1916, it was imperative to coordinate efforts in campaigns and thus the wristwatch became an item that was invaluable in this sense, although wristwatches had been around, particularly in European markets since the 1850s, this was when the wristwatch found its way into the American market.

Let’s look at the area of diffusion process again.

The early adopters, on the other hand are those who look to the innovators, and people who can use word of mouth to illustrate the innovation. These could also include means of distribution and once the product can be seen, it can be purchased by those early adopters. Therefore, key to the early marketing strategy is that of distribution or visibility.

The early majority are keen to purchase products as they have been used, as in tried and tested and been around for a bit. At this point, the diffusion process is almost complete. It’s worth mentioning that a product can spend a good part of its lifespan here. For example, with wristwatches, let’s take the year of 1880 as a typical year when early adopters were using the technology, the years between 1880 and 1900 when the early majority were using watches. From 1900 to 1940, the late majority were purchasing wristwatches, and when your watch broke, you had it repaired or bought a new one. Everyone has a wristwatch and the object has become part of every day life.

From the UK perspective, in the 1850s, local time was being replaced with standard time, and this became law in 1880 by Royal Assent. We’ve considered the ‘innovators’, those who kept clocks, portable clocks, watches in order to tell the time, rather than having to rely on the more traditional sundial. These are the people who like ‘novel’, they purchase new technologies and will pay premium for the product. They are also the influencers of opinion. As we’ve seen, in the past, it has been royal houses and houses of wealth who can afford such luxuries. In contemporary society we have ‘influencers’ and ‘celebrities’.